Uganda is one of the most diverse and dynamic countries in Africa. Rivers flow through the country’s south, spilling into and out of countless small and large lakes, and combining with the region’s abundant rainfall to water its fertile soil. In the north, where rain and waterways are rarer, the land supports herds of domesticated animals—goats, cattle, and sheep—and pastoralism has historically formed the basis of the region’s economy. In between, snowcapped mountains rise in the east, separating the landlocked country from neighboring Kenya, while the continent’s largest oil reserves lie beneath the surface in Uganda’s west.

Uganda’s people—the most ethnically diverse population in the world, with more than 24 ethnic groups—speak more than 40 languages. The country has one of the world’s fastest growing populations as well: More than 1.5 million Ugandan babies are born each year.

This diversity and dynamism have inspired ambitious goals. In its 2015/16 to 2019/20 National Development Plan, the Ugandan government, hoping to reap the harvest of the country’s vast demographic dividend, outlined its aim of achieving lower-middle-income status by 2020, and upper-middle-income status by 2040.

But significant challenges, including the poor condition of the country’s educational system, continue to frustrate these lofty aspirations. Aware of the system’s many problems, the Ugandan government, with assistance from the international community, has taken notable steps to reform and improve it. But problems persist, exacerbated by uncontrolled population growth, creeping authoritarianism, smoldering internal and external conflicts, and a history of underdevelopment and neglect that is rooted in colonial exploitation and which continues in a modified form to this day.

Uganda is one of the youngest and fastest growing countries in the world. Since its independence from the British in 1962, Uganda has seen its population increase more than fivefold, growing from just under eight million in 1965 to more than 44 million in 2019. In the next 30 years, its population is expected to double again, reaching nearly 90 million by 2050, making Uganda the 21 st most populous country in the world, with a population density comparable to that of South Korea. Rapid population growth has meant a ballooning youth population. Nearly half (48 percent) of all Ugandans are under the age of 14. Another 20 percent is between the ages of 15 and 24.

While government planners had hoped to harness these demographic trends, the explosive population growth—described by one diplomat in Kampala, Uganda’s capital, as a “demographic time bomb”—instead threatens to overwhelm the country’s natural and public resources. Pedestrians and motor vehicles already crowd Kampala’s main streets, making congestion a recurrent public concern. On the capital’s outskirts, shantytowns have spread rapidly, as the nation’s housing stock has failed to keep up with demand. And despite Uganda’s reputation as “Africa’s breadbasket,” experts worry that the country will not be able to produce enough food to feed its massive population. Agricultural productivity falls with each new generation, as parents divide their land among their children into smaller and smaller plots.

Population growth also threatens to overwhelm gains made by the economy, which, despite impressive growth rates over the past several decades, is still weak by international standards. In 2018, Uganda’s per capita gross domestic product (GDP) was less than half of that for all of Africa. With more than 1.5 million people born annually, the pace at which new jobs are created is far too slow to allow the labor market to absorb the large number of Ugandan youths entering it each year. According to the African Development Bank Group, Ugandan youths account for around 83 percent of all unemployed Ugandans, the highest youth unemployment rate in all of Africa.

Uncontrolled population growth has also hindered efforts to eliminate poverty in Uganda, one of the continent’s poorest countries. Despite significant reductions in poverty, one person in five still lives below the poverty line. As one expert puts it, “no country has managed to substantially reduce poverty with birth rates of that order.”

This growth has also significantly strained the country’s public and social services. There is only one doctor for every 5,950 Ugandans, with most doctors concentrated in the country’s urban areas. It has also placed extreme stress on the country’s educational system, so that access, quality, and outcomes at almost all levels of education are poor. Although students fill classrooms, qualified teachers are hard to find. And despite overcrowding, access—especially to secondary and tertiary education—remains limited. Learning facilities are often inadequate, with many schools lacking basic toilets and washrooms. And despite experts warning that graduates of Uganda’s educational system lack the skills needed in the modern economy, these problems are even more pronounced in the country’s outlying regions and among certain vulnerable populations, such as refugees, internally displaced persons, and the poor. At the root of many of these issues is chronic government underfunding and mismanagement, problems that have only worsened over time. These problems will be discussed in greater detail below.

Effective government responses to the growing population, educational deficits, and other challenges are hindered by weak democratic institutions, widespread corruption, and the state’s retreat from providing public services. The roots of many of these governing problems extend well into Uganda’s turbulent political and colonial past.

Between 1894 and 1962, the British Empire administered the territory of present-day Uganda as a protectorate. While this status allowed the people of Uganda a degree of self-government not available to the Empire’s colonies, British administrators still exercised control through an implicit policy of ethnic and religious favoritism. Efforts aimed at developing the country’s own people and its domestic resources were minimal and often confined to a select few. Education provided by the colonial state was restricted to the training of a small number of local administrators.

The British politicization of ethnic and religious differences (divide and conquer) had lasting consequences, fueling many of the violent conflicts that have ignited along ethnic and religious fault lines in the decades following Uganda’s independence. In the 1970s, the notoriously ruthless military dictatorship of Idi Amin devastated the country’s population and undermined its fledgling democratic institutions. Politically inspired violence during Amin’s reign claimed the lives of around 300,000 Ugandans. He also expelled the country’s entrepreneurial Indian minority as part of what he termed “economic war.”

The terror of Amin’s reign did not spare the educational system, including students, teachers, and staff. In 1972, Frank Kalimuzo, vice chancellor of Uganda’s top educational institution, Makerere University, disappeared mysteriously after rousing Amin’s ire. In 1976, police and military personnel shot and killed more than 100 Makerere students who were demonstrating against the government. Nor did Amin’s reign spare the education system’s quality and reputation. As statutory chancellor of Makerere University, the infamously lawless general conferred upon himself an honorary Doctorate of Law.

His overthrow in 1979 was not lamented. A retrospective written on the 50-year anniversary of Ugandan independence sums up well the country’s collective memory of Amin’s reign. It was as if the “soul of the country was being ripped out.” Unfortunately, the second regime of Milton Obote—Uganda’s first prime minister and president, whom Amin had overthrown—was hardly an improvement.

But the rise to power of Uganda’s current leader, President Yoweri Museveni, following a successful military coup in 1986, seemed to mark a new and more peaceful and prosperous era. And in the beginning, it did. Ugandans and the international community lauded the early years of Museveni’s rule as a respite from years of chaos and bloodshed. But this assessment quickly began to wane, as violent conflict continued to grip large portions of the country and the government became increasingly authoritarian. Enthusiasm for Museveni has continued to fall, as time has amply proved his government’s inability to address many of the country’s problems, including those of its educational system.

Uganda’s current political system has been described as a hybrid regime, possessing a contradictory mix of democratic and authoritarian traits and selectively promoting or curtailing civil rights and political freedoms. For example, in 2005, Museveni gave in to mounting public pressure and legalized political parties, but only in exchange for an expansion of executive powers, including the elimination of presidential term limits. In late 2017, presidential age limits were also removed, opening the door for a sixth presidential term for Museveni in 2021, when he will be 77.

These authoritarian tendencies are responsible for the country’s poor record on human rights and political liberties. International organizations have recorded a litany of human rights abuses committed by both the Ugandan government and rebel groups during the more than two decades-long conflict in northern Uganda. Reports of arbitrary detainment and torture by state police and military forces have circulated for years, although such reports have been fewer over the past two decades. And draconian anti-LGBTQ legislation, which in an earlier form had threatened offenders with life imprisonment or death, was only invalidated by a ruling from one of Uganda’s highest courts. The legislation continues to be revived from time to time in Uganda’s parliament.

In many ways, Museveni’s relaxation of government control has gone furthest in the marketplace. His early eagerness to liberalize the economy and open the country to foreign capital earned him the esteem and support of the international community, and gross domestic product (GDP) growth has been strong under his leadership.

But Uganda’s economy remains heavily dependent on foreign direct investment and external loans, with much of foreign aid imposing economic liberalization requirements. For example, in 1987, in exchange for the financial support of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Museveni agreed to implement the Economic Recovery Program, which required significant structural adjustments, including the relaxation of price controls and the privatization of public assets and services. The reforms that followed this and other foreign aid agreements have led to the state’s withdrawal from providing many social services. The introduction of cost-sharing radically transformed the education sector, with individuals and private organizations bearing a growing share of education costs. Observers attribute most of the education system’s current troubles to this retreat of the state.

Uganda’s strong support of regional free trade has had a more positive impact on the country’s educational system. Under Museveni’s leadership, Uganda has been an advocate of the East African Community (EAC), which established an East African common market in 2010, and aspires to establish a monetary and political union of several East African countries in the coming decades.

Economic liberalization has also provided opportunities for corruption, which is rampant at nearly all levels of Ugandan society. Public officials misappropriate public funds and distribute political and military positions to relatives and acquaintances, or in exchange for favors. Despite highly publicized corruption trials targeting low-level bureaucrats, corruption remains largely ignored, although it exists at the highest levels of government. Concerns over elite corruption and the misappropriation of aid funds led the United Kingdom to temporarily suspend aid to Uganda in 2010.

Corruption and related patronage networks have even strained internal relations in the country. Museveni’s apparent favoritism in political and military appointments toward ethnic groups from western Uganda—Museveni’s home region—have helped stoke tensions between Uganda’s varying regions and ethnicities. In the education sector, reports surface often of ministry officials embezzling funds meant for schools and students, or of university administrators forging degrees for a fee.

In the 1990s, falling global commodity prices accelerated Uganda’s economic liberalization plans. With the country’s large agricultural sector stumbling, falling tax revenues significantly complicated the government’s financial situation. But starting in 2006, a string of discoveries revealed oil reserves underground, raising hopes that Uganda could free itself from its long-standing reliance on the weather and global food prices. Although oil has yet to flow out of Uganda—oil production is expected to begin in 2021—the discoveries have already placed a premium on education relevant to the oil and gas industry.

Observers have highlighted the importance of managing these oil reserves in a responsible and equitable fashion if Uganda wishes to avoid the “waste, corruption, and environmental catastrophe and conflict” seen in other fast-growing oil-producing countries. Good governance will also be essential to Uganda as a whole, if it wishes to rectify the problems of its past and achieve its full potential.

At times, the Museveni government has been willing to enact ambitious reforms aimed at addressing some of these issues. In the educational system, significant reforms—discussed in greater detail below—have been met with mixed success. But in recent years, the government’s actions and public statements have not signaled a willingness or ability to make the changes needed to address these problems. With the unfolding of COVID-19 in the country, and Museveni already declaring his intent to run for re-election in 2021, it’s unclear when the conditions will be right for more meaningful change.

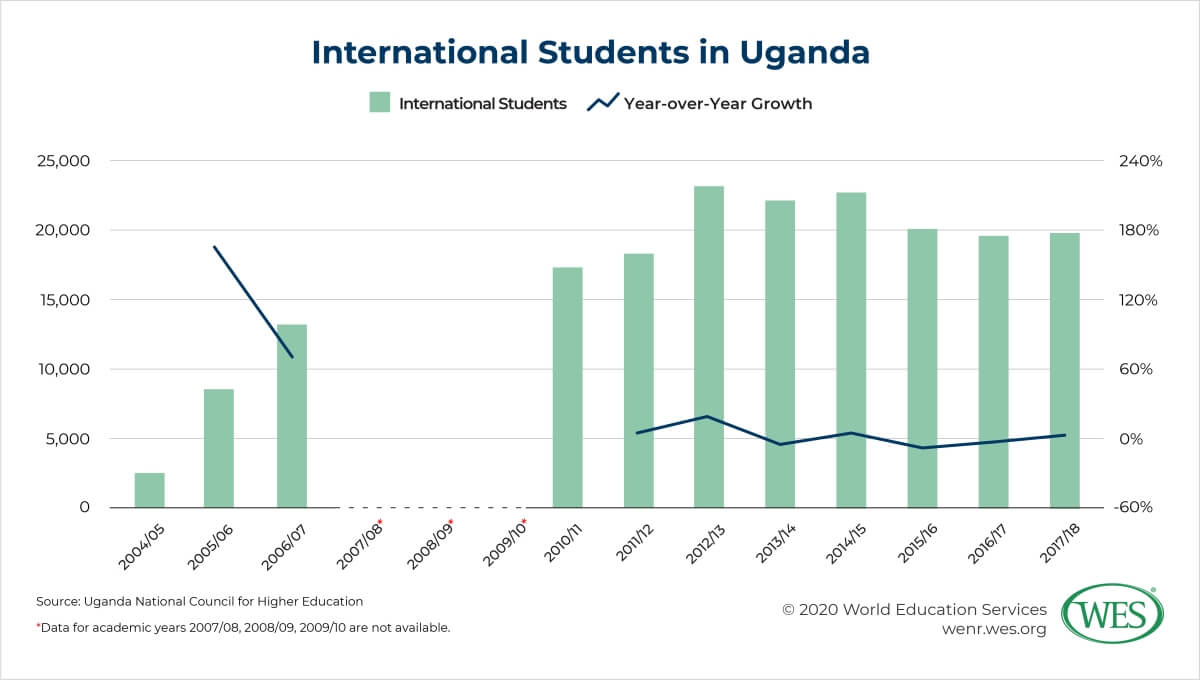

The number of international students enrolled in Ugandan universities skyrocketed in the first decade of the 21 st century. But as the second decade progressed, growth appeared to stagnate or even decline, as the country’s underfunded higher education system strained under growing demand—both domestic and international—for university seats.

Data on international students in Uganda are often not readily available, with numbers scattered through a series of State of Higher Education and Training reports published by Uganda’s National Council for Higher Education (NCHE). An unfortunate gap in the data exists for the 2007/08 to 2009/10 academic years. While NCHE intended to publish the reports annually beginning with the 2005/06 academic year, it never released the reports, or the accompanying data, for these years.

But the data which are available reveal dramatic growth rates in the mid-2000s. Between 2004/05 and 2006/07, the number of international students in Uganda more than quadrupled, growing from just under 3,000 to nearly 13,000. Thereafter, growth continued, although at a slower rate. In 2010/11, when data are next available, the number of international students in Uganda reached more than 16,000. In 2012/13, it peaked at just over 21,000.

But since then, growth has stagnated. In 2017/18, the latest year for which data are available, the number of international students in Uganda had fallen 10 percent from its peak, to just under 19,000.

The relative affordability and quality of Uganda’s academic institutions and a series of domestic and regional educational mobility initiatives helped drive much of the explosive growth of the mid-2000s. The low tuition fees and diverse course offerings of Uganda’s universities attract students from neighboring countries, who also find Uganda’s modest cost of living and relative safety appealing. For students from Kenya, the largest source of international students in Uganda, the similarity of Uganda’s educational system to its own also eases the transition. Furthermore, unique to the region, Ugandan universities are able to accommodate special-needs students, although much work in this area remains.

Educational mobility initiatives have also facilitated and promoted the cross-border movement of students. The government of Uganda has long sought to position itself as an attractive study destination for students in east and southern Africa. In 2007, Uganda’s National Export Strategy identified educational services as a priority export sector. In 2010, the Commonwealth Secretariat and the Uganda Export Promotion Board commissioned the Marketing Uganda HE project, which aimed at improving the competitiveness of the country’s higher education export sector, with a focus on recruitment from East African countries and Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) member states.

Financial considerations partly drive the interest of the Ugandan government in international education. NCHE’s 2006/07 report noted that education exports contributed US$30.7 million to the Ugandan economy, making education the country’s fourth-largest export sector.

Regional cooperation has supplemented these domestic initiatives. Efforts to harmonize the educational systems of East African Community (EAC) member states aim at ensuring the intra-regional comparability of qualifications, which as European experience suggests, helps to facilitate intra-regional mobility. In 2014, tuition fees for students from some EAC member states were also harmonized. As a result, international students from Kenya and Rwanda studying in Uganda pay the same fees as domestic students.

Despite these efforts, the continued ability of Ugandan universities to attract international students remains uncertain. Over the past several decades, underfunding has caused the quality of Ugandan universities to decline sharply, increasingly tarnishing their once sterling international reputation. The 2011/12 NCHE report, in comments on the relative slowdown seen that year, is blunt: “As a result of many factors, including the perception that the quality of Uganda’s higher education is declining due to a number of reasons, particularly funding, the percentage of foreign students coming to Uganda [out of all students enrolled in Ugandan universities] is still declining since 2006.”

Most international students in Uganda come from regional neighbors. In addition to Kenya, sizable numbers come from Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, and Tanzania.

Most international students attend private universities, with Kampala International University and Kampala University hosting 4,500 and 2,500 international students respectively in 2015/16. With insufficient funding causing the infrastructure of public universities to deteriorate, international student interest has declined. At Makerere University, the most popular public university among international students, international student enrollments fell from a high of 2,444 in 2010/11, to 449 in 2015/16.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had severe consequences for the many international students still in Uganda. Although Museveni ordered all institutions of learning, including universities, to close effective March 20, many international students remained in Uganda, as fear of cross-border transmission greatly reduced the feasibility of international travel. With the global economy collapsing and the financial resources of many international students and their families drying up, some have reported difficulties affording basic necessities, such as housing, water, and food.

Local reports suggest that international students are turning to their universities and the Ugandan government for support. Although some universities, such as Makerere University, have been able to provide some assistance to their international students, the well-being of international students at institutions elsewhere is less secure.

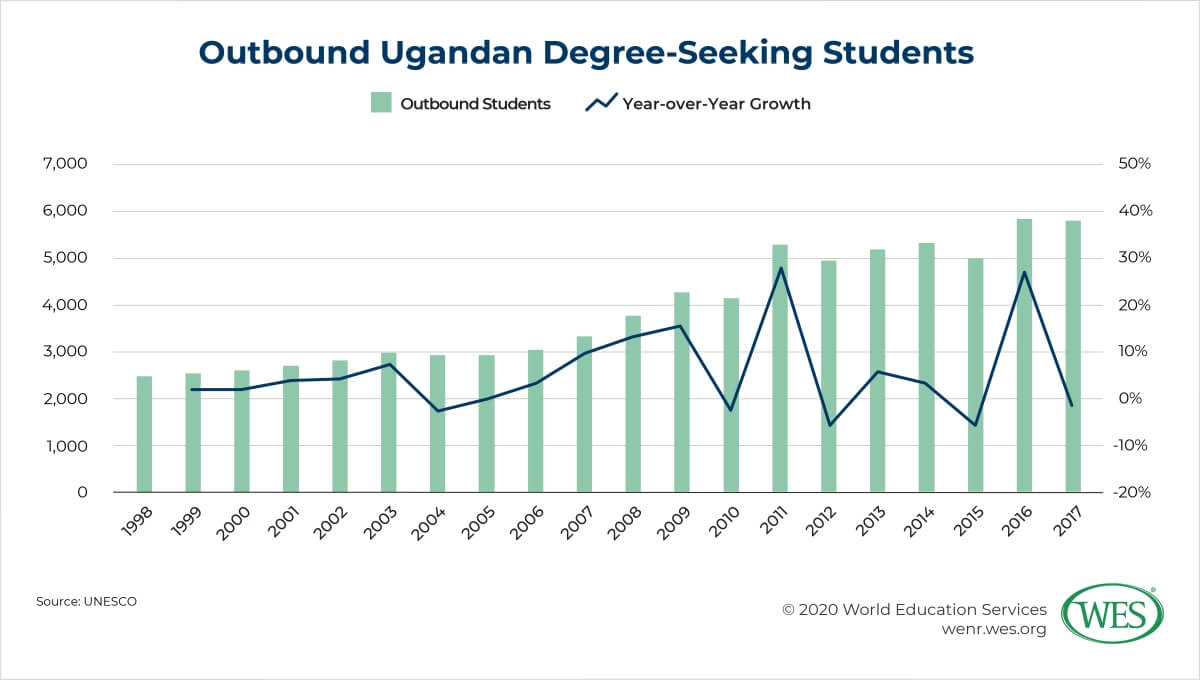

Despite Uganda’s large youth population and under-resourced domestic higher education system, the country is not currently a major source of international students. But changing economic and educational conditions may portend significant growth in the years to come.

Despite having a university-age population of more than 3.4 million in 2014, only a small number of Ugandans head overseas to study each year. In 2017, the latest year for which UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) data are available, fewer than 6,000 Ugandan students studied for a university degree internationally.

While the number of Ugandan students studying abroad has more than doubled since 2000, growth has largely stalled in recent years. In 2017, only around 500 more Ugandan students were studying overseas than in 2011.

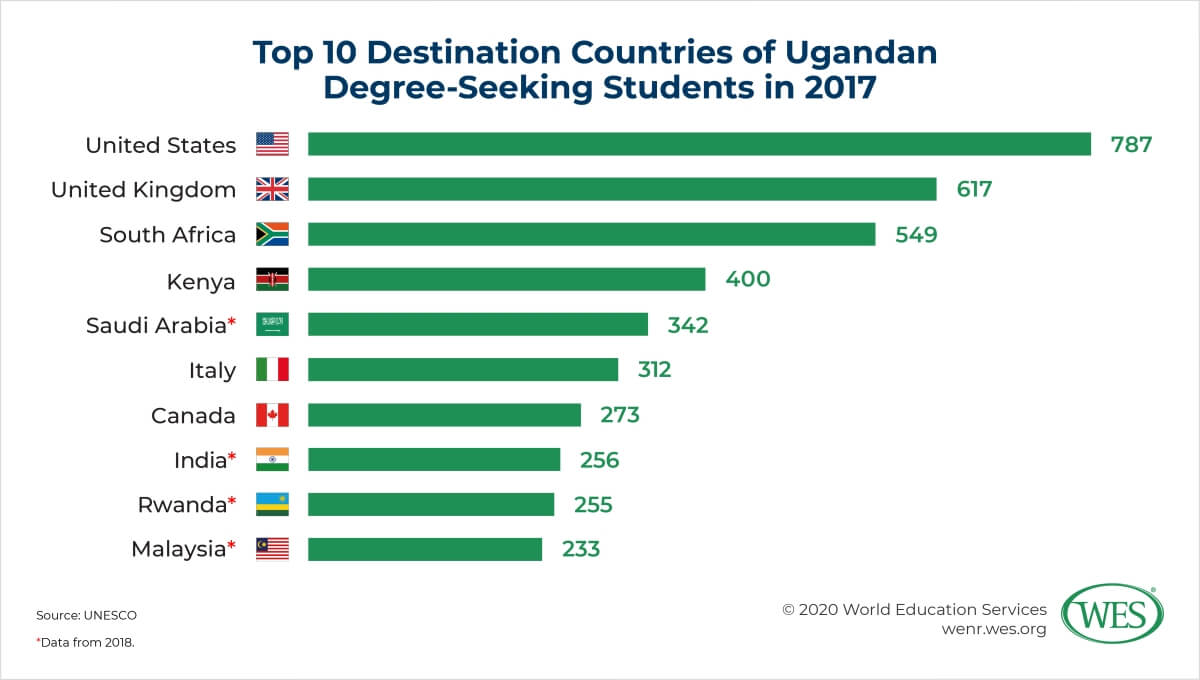

Those Ugandan students who do travel overseas tend to study in English-speaking countries. The United States and the U.K. are the top two destination countries for Ugandan students, hosting 787 and 617 Ugandan students in 2017, respectively. South Africa (549), the continent’s educational powerhouse, follows. Other EAC countries, such as Kenya (400) and Rwanda (255), are also popular.

Muslim majority nations, such as Saudi Arabia and Malaysia, also attract significant numbers of Ugandan students, hosting 342 and 233 Ugandan students respectively in 2018. Uganda’s sizable Muslim population and the country’s membership in the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) have played an influential role in funneling Ugandan students to these countries. The number of Ugandan students studying in Saudi Arabia expanded dramatically following the Saudi government’s introduction of full scholarships for Ugandan students around 2012.

In addition to these outbound students, more than 7,000 Ugandan students enrolled in U.K. transnational education (TNE) programs in the 2018/19 academic year, according to data from the U.K.’s Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA).

Financial and educational conditions currently restrict the pool of students able to study overseas. Uganda’s small middle class—the country’s per capita GDP was just over US$750 in 2019—and low secondary school graduation rates mean that the number of college-age students financially able and educationally qualified to study overseas remains small.

However, there are reasons to believe that more Ugandans will study internationally in the future. The continued growth of Uganda’s youth population is likely to exacerbate already widespread quality issues at Uganda’s universities. Severe overcrowding in the country’s universities, a shortage of qualified professors, and chronic underfunding are likely to push more and more Ugandan students overseas.

And although it is small today, Uganda’s middle class is currently growing faster than the population as a whole. Rising levels of expendable income will enable more Ugandan students to afford the heightened costs of a university education abroad.

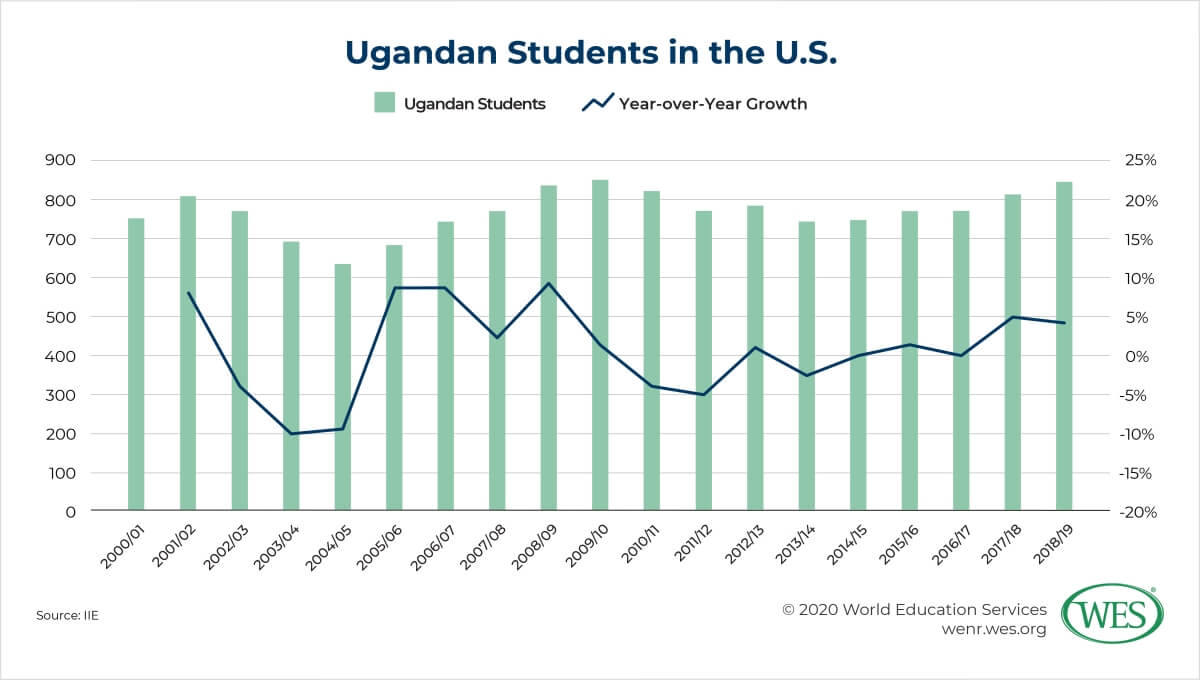

Ugandan students make up a small proportion of all international students in both the U.S. and Canada. But in recent years, growth trends in the two countries have diverged sharply. Differences in their recruitment and marketing practices, as well as their political climate, likely account for some of that divergence.

In comparison with the massive U.S. international student population—more than one million international students studied in the U.S. last year—the number of Ugandan students enrolled at U.S. colleges and universities is minuscule, reaching just 848 in 2018/19, according to Open Doors data from the Institute of International Education (IIE). Over the past two decades, growth in the number of Ugandan students studying in the U.S. has also been minimal. Since 2000, that number has fluctuated between roughly 650 and 850 students a year.

The U.S. attracts both undergraduate and graduate students. In the latest academic year, nearly equal proportions, 42 percent in both cases, were enrolled in undergraduate and graduate programs. The remainder were enrolled in the Optional Practical Training (OPT) program (13 percent) and non-degree programs (3 percent).

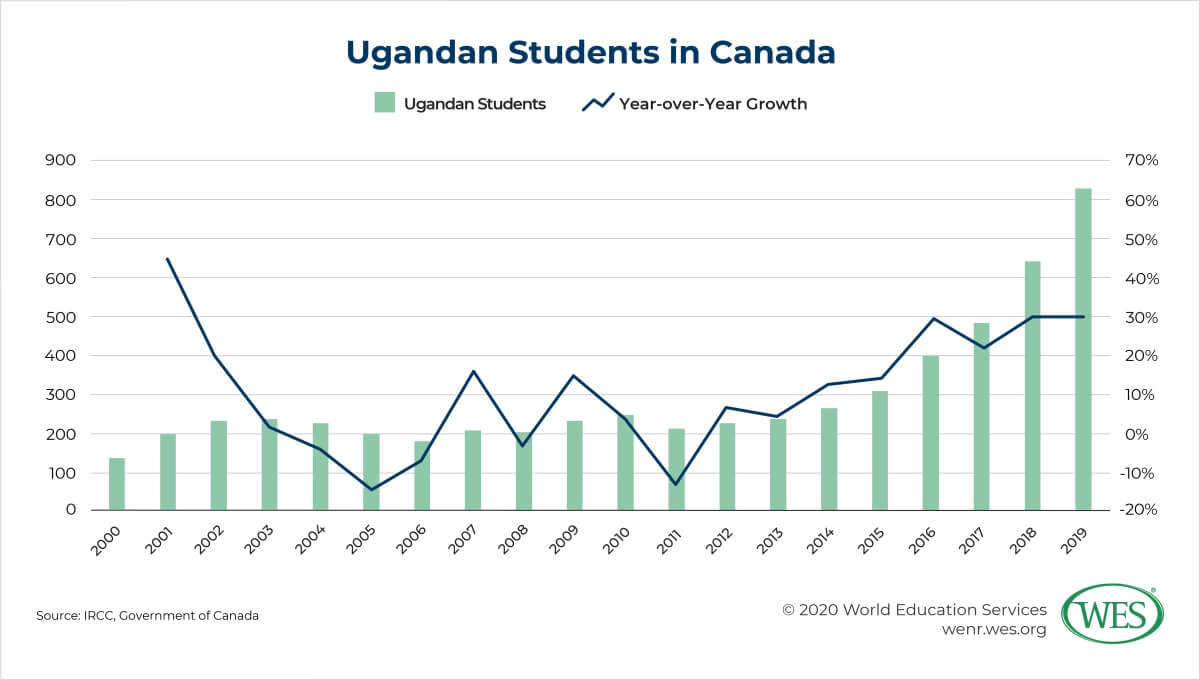

The recent experience of Canada contrasts sharply with that of the U.S. Although the number of Ugandan students studying in Canada remains small, it has trended sharply upward in recent years, more than doubling between 2015 and 2019, from 310 to 825. Year-over-year growth has accelerated since 2013, with the number rising 30 percent between 2018 and 2019.

Effective marketing may partly explain the strong performance of Canada relative to that of the U.S. Agents in Uganda have praised Canada’s in-country recruiting and promotional efforts, which are coordinated by Canada’s consulate in Uganda. The relative affordability of Canadian universities may also appeal to Ugandan students. Finally, Canada’s more open attitude to citizens of other countries has likely helped foster among Ugandan students a perception of Canada as a welcoming place to further their education.

For more than a decade, China has leveraged its economic might and its improving educational infrastructure in a bid to exert soft power on the African continent. In the area of education, these efforts have included the funding of skills training and capacity building projects in African countries, and the promotion of international student mobility to universities in China.

Guiding these initiatives is a concerted campaign by the Chinese government to win the hearts and minds of the citizens and students of African countries so that they are able to “tell China’s story well and spread China’s voice,” as the Chinese Ministry of Education puts it. But critics, and even some recipients of those educational benefits, worry that the aid will keep African countries trapped in a position of dependency on China.

China has not overlooked Uganda in its public diplomacy efforts. Both the Chinese government and its corporations have invested significant financial and technical resources in Uganda and the Ugandan people. China is the top source of direct foreign investment in Uganda, and Chinese companies are estimated to have created at least 18,000 jobs for Ugandans in the country.

The Chinese government is also engaged in several significant educational initiatives throughout Uganda. In 2014, China opened the first Confucius Institute (CI) in Uganda in partnership with Makerere University. CI’s mission is “to provide a conducive environment for training, research and dissemination activities in view of bridging the communication gap, enhancing interaction, promoting cultural exchange and strengthening friendship ties between the peoples of Uganda and China.”

Makerere University later introduced the nation’s first Bachelor of Chinese and Asian Studies, developed in cooperation with CI. Although still awaiting approval by the National Council for Higher Education (NCHE), the three-year program seeks to ultimately “provide learners with certified proficiency in Mandarin and competence in understanding its linguistic, cultural and literacy aspects.” Mandarin is also being taught to younger students. A 2018 pilot program, supported by the Chinese government, introduced compulsory Mandarin classes to 35 senior secondary schools, with plans to expand in the future.

Other educational initiatives require students to travel further afield. In 2019, the Chinese government awarded 99 full scholarships to Ugandan students to study in China. The scholarships cover the entire cost of tuition, living, health care, and air travel.

At first glance these initiatives appear to have achieved impressive results. While UIS does not publish data on Ugandan mobility to China, reports from Xinhua, China’s state-controlled press agency, suggest that Ugandan students are heading to China in numbers comparable to those attending universities in the U.S. and the U.K. And opinion polls suggest that the majority of Ugandans view China’s economic and political influence positively.

But some Ugandan graduates of Chinese universities paint a more complicated picture of China’s close involvement in their country. Interviews with current and former Ugandan students in China reveal “a great deal of skepticism among graduates around China’s role in Uganda, with several graduates voicing negative opinions of China’s economic involvement in the country.” One former student remarked that, “From my interactions and my analysis, it feels like they are here for them, kind of like they are colonizing us.”

One Ugandan student stated that in China itself “There is racism … [it] is right there, but no one wants to talk about, nobody cares about it, everyone is just indifferent. Actually that’s one of the reasons why I wanted to leave China.” The overseas experiences of these Ugandan students have colored their perceptions of China’s influence back home.

Despite these reservations, China’s overwhelming economic might suggests that its influence in Uganda is here to stay.

Uganda’s educational system has expanded remarkably over the past few decades, but significant access and quality issues remain. To address these problems, and to better align the educational system with the needs of the modern global economy, the government of Uganda introduced and implemented a series of ambitious reforms. Although the reforms substantially expanded access to certain levels of education in Uganda, critics allege that in the rush to boost enrollment numbers, educational quality has suffered.

Educational reform in Uganda has a long history. Glaring inadequacies in the colonial educational system—less than 2,000 Ugandan students were enrolled at the Ordinary Level at independence in 1962—spurred the newly independent government to immediately attempt its reform. Early efforts aimed at two long-term policy goals: universal elementary education, and the provision of an education able to equip students with the skills required to power Uganda’s growing economy and political administration. The resulting measures—which included the public construction of classrooms throughout the country—achieved modest success. By 1970, Ordinary Level enrollment had grown to 30,000.

However, the political turmoil of the 1970s and early 1980s upset these early ambitions, freezing reform efforts and severely eroding the quality of education at all levels throughout Uganda. But as the worst of the political unrest began to subside following Museveni’s rise to power in 1986, a growing awareness of the inadequacies of the current system and the gap existing between educational outcomes and the needs of economic development prompted a resumption of the reforms first introduced decades earlier.

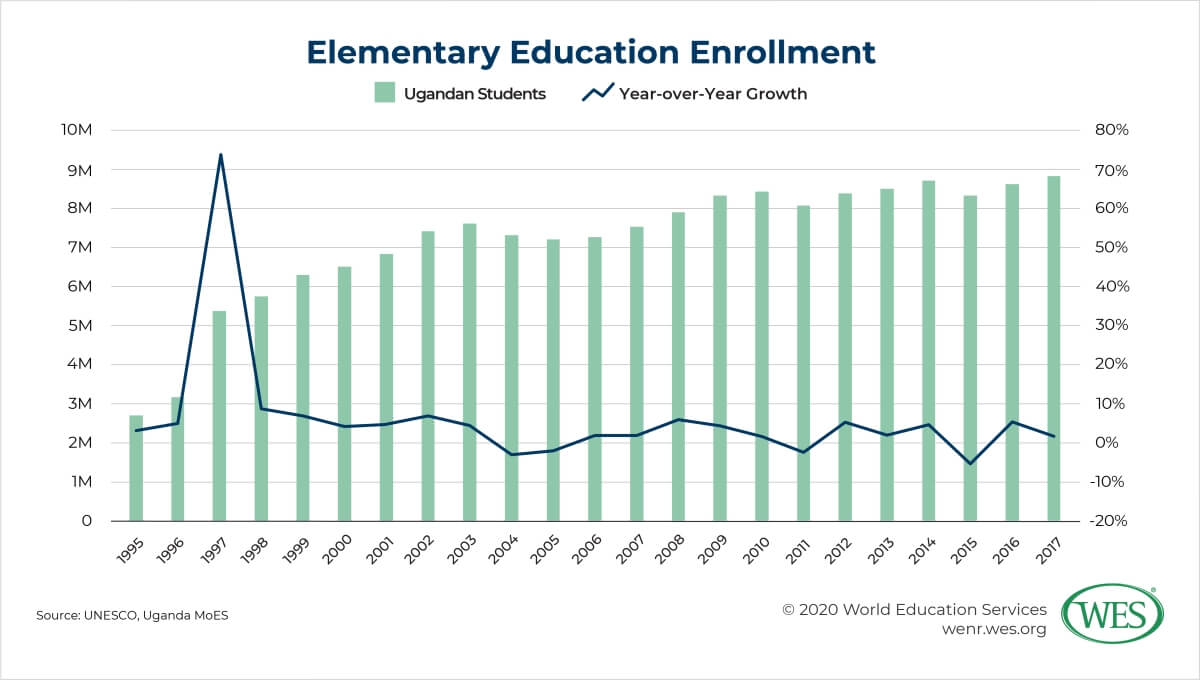

The first significant result of these renewed reform efforts was the introduction of Universal Primary Education (UPE) in 1997. The UPE initiative initially promised tuition-free elementary education to four children per Ugandan family. The government eventually extended tuition-free education to every Ugandan of elementary school age, a concession to the needs of Uganda’s large families, who, from the policy’s initial rollout, had been sending more than four children to school simultaneously. The Ugandan government hoped that UPE would help reduce poverty and develop the country’s vast store of human resources.

The program’s success in expanding access to elementary education is undeniable. In the first year following its introduction, elementary enrollment grew by nearly 75 percent to 5.3 million. By 2003, that number had increased to 7.3 million, well over double its size in 1996. The gross enrollment ratio at the elementary level shot up from 71 percent in 1996, to 118 percent the next year.

Despite the stunning successes of the UPE program, significant problems persist. Growing enrollment rates have not been accompanied by rising completion rates. Uganda has long had one of the highest elementary school dropout rates in the world, a problem that UPE initially exacerbated. By 2003, the first year that an entire cohort had been educated at the elementary school level under the UPE, a staggering 78 percent of all Ugandan students had dropped out before completing their elementary education, up from 62 percent in 2000, according to UIS data. Although conditions have since improved, high dropout rates persist. In 2016, nearly two-thirds (65 percent) of all students dropped out of elementary education before completion.

Other education indicators suggest that expanded elementary school enrollment may have come at the expense of educational quality. In Uganda’s schools today, students crowd classrooms, overwhelming the country’s understaffed teacher corps. There are around 43 pupils per teacher at the elementary level, well above the world average of 23, and even above the sub-Saharan African average of 38, according to UIS data. The negative effects of the country’s teacher shortage are exacerbated by high rates of teacher absenteeism. In more than half of all Ugandan schools, at least three in five teachers are absent. School infrastructure is also often inadequate, with many schools lacking toilets and bathrooms, as noted earlier. In certain regions of the country, such as northern and eastern Uganda, conditions are even worse. As a result, numeracy and literacy rates remain low. Today, just two in five students who complete elementary school are literate.

A March 2014 report on Uganda’s progress in achieving universal elementary education identified widespread poverty, a lack of nearby schools, and inadequate and overcrowded learning facilities as the most critical drivers of the country’s high dropout rates. The expenses incurred by families sending their children to school in Uganda can be considerable. Although UPE guarantees tuition-free elementary education to all Ugandan children, other expenses, such as school uniforms, books, and even “school development funds” for projects such as building maintenance, must be provided by the students and their families. For many of Uganda’s poorest families, some of whom live on as little as one dollar a day, these supplemental expenses pose an insurmountable barrier.

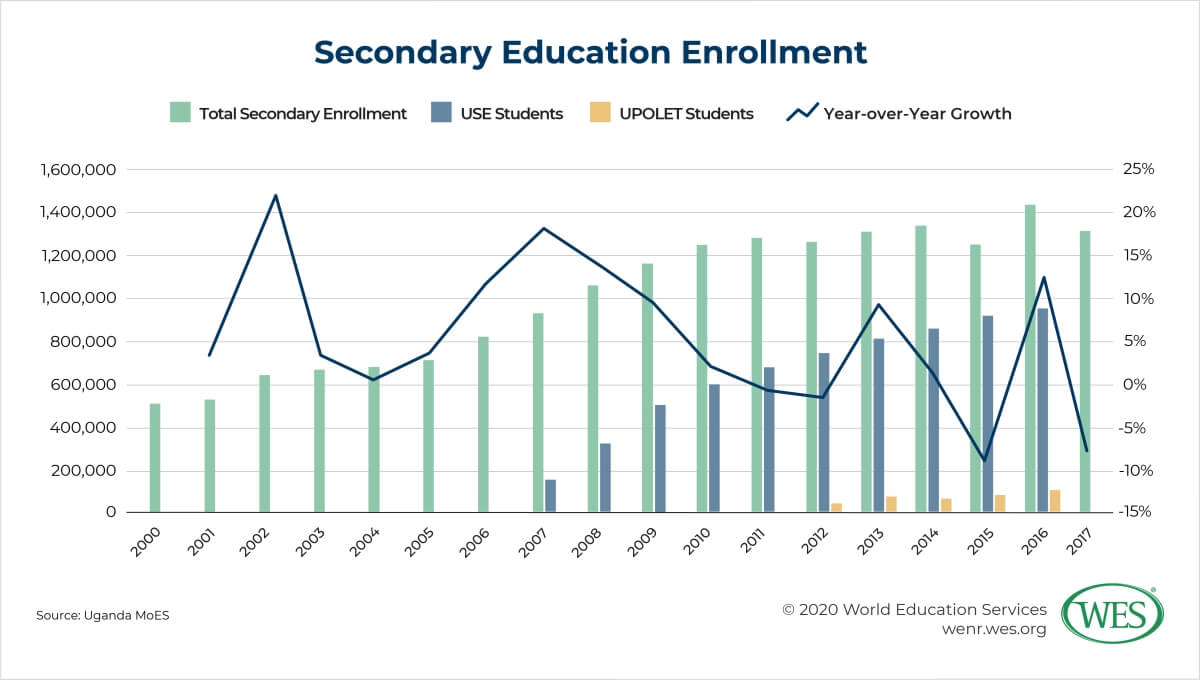

In 2007, a decade after the start of UPE, the government of Uganda introduced the Universal Post Primary Education and Training (UPPET) program, better known as the Universal Secondary Education (USE) program. The program sought to extend free, high-quality lower secondary education to Ugandans who had successfully completed elementary education. In 2012, the government introduced the Universal Post O Level Education and Training (UPOLET) program, which also extended free upper secondary education to those who had completed elementary education.

While USE and UPOLET aimed at extending free secondary education to all eligible Ugandans, the programs did not replace the previously prevailing fee-based model of secondary education. Fee-based schools, both public and private, continue to exist alongside tuition-free USE and UPOLET schools, and often appeal to wealthier families who are able to spend more for better learning facilities. The USE policy also included a public private partnership (PPP) program, which allowed private schools to participate in the USE program, with the government covering some of the cost of tuition for students choosing to enroll at participating private secondary schools. Over time, the proportion of secondary students enrolled in USE schools, both public and private, has increased.

Initial assessments of the programs’ performance, especially the USE program, were positive. In the words of the then director of basic education at Uganda’s Ministry of Education, the USE program had, by 2010, “ushered in an ambitious and comprehensive reform program to provide universal access to quality post primary education and training which has played a critical role in providing future workers with competencies and knowledge required for increase in productivity and labor mobility.” By 2016, more than one million students were participating in tuition-free secondary school through either the USE or UPOLET programs.

But enrollment figures suggest that the success of the programs in expanding overall access to secondary education has been mixed. The years immediately following USE’s introduction saw steady growth, with total secondary enrollment increasing from around 815,000 in 2006, to nearly 1.2 million in 2009, according to the Ministry of Education and Sports (MoES) statistics. But growth slowed considerably thereafter. After peaking at just under 1.5 million in 2016, enrollment declined to less than 1.4 million the next year.

This modest, uneven growth was far from enough to achieve one of the programs’ central aims: universal enrollment. In 2017, a decade after USE’s introduction, just a quarter of secondary school-age Ugandans were enrolled in school. In the country’s outlying regions, conditions were even worse. In Lango and Karamoja, two northern sub-regions, just 10 percent of the relevant age group attended secondary schools.

Quality and educational outcomes also remain poor. In 2017, two out of five secondary school teachers did not possess an undergraduate degree. Student-to-teacher ratios are still high. In 2013, more than one-third of UPPET classrooms had more than 60 students.

Graduation rates are even more shocking. In 2016, just 11 percent of the relevant age group graduated from upper secondary school. And government officials and business leaders worry that those who do graduate are inadequately prepared for employment or university education.

Many of the problems at both the elementary and secondary levels result from inadequate public funding. Despite Uganda’s quickly growing youth population, spending on education as a share of total government expenditure has declined sharply, falling from around 25 percent in the early 2000s to just 11 percent in 2018, according to the World Bank. In 2019, the National Planning Authority (NPA), a constitutionally mandated development planning agency, decried the government’s inadequate spending on elementary education, noting that the government would need to more than double its per student spending if it ever wished to fulfill the early promises of the UPE program.

At the secondary level, funding declines are even more extreme. A growing percentage of the money the government spends on education is being redirected from secondary to elementary education.

Given these trends, the words of the NPA’s executive director, Joseph Muvawala, could easily be extended to secondary education: “Given the massive resources required to improve the quality of UPE, it remains an illusion that the quality of education will improve under the current financing arrangements.”

Uganda is divided into four administrative regions, 15 sub-regions, 127 districts, and various other subdivisions. Population growth and the continual reorganization of local governments have resulted in a proliferation of districts, which grew from 16 in 1959 to 121 in 2017. Five traditional kingdoms, restored in 1993, also exist alongside the central government. Despite continual calls for a decentralized, federal constitution, particularly from the kingdom of Buganda, these kingdoms are only authorized to act as cultural authorities, and lack real political and administrative power.

Despite the country’s immense ethnic and administrative diversity, executive, legislative, and judicial power in Uganda is largely concentrated in the nation’s capital, Kampala, with the jurisdiction of the nation’s central ministries and other political institutions extending to the entire country. The administration of education in Uganda is also centralized. The MoES, a cabinet-level ministry, manages and oversees all levels of education throughout the country. The mission of MoES is “To provide for technical support, guide, coordinate, regulate, and promote the delivery of quality education and sports to all persons in Uganda; for national integration, individual and national development.”

The MoES also directly or indirectly governs the following bodies, whose mandates are restricted to the management of specific sectors of the country’s education system:

The government of Uganda, through the MoES, funds elementary and secondary schools that participate in the UPE, USE, and UPOLET programs. A large number of intergovernmental organizations and agencies—such as UNESCO and UNICEF—and foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are also active in funding and supporting education in Uganda.

The MoES regulates more than 30,000 pre-elementary, elementary, and secondary institutions spread throughout Uganda. At the elementary level, more than 59 percent of the more than 20,000 schools in 2017 are government-owned and -supported. The remainder are private, administered by religious bodies, both Christian and Muslim, entrepreneurs and investors, or local communities, among others.

There were significantly fewer secondary schools, just 3,000 in 2017, and of those, nearly two-thirds were private. However, the government owns more than 60 percent of the secondary schools participating in the USE program. USE schools made up around half of all secondary schools in 2017.

As discussed above, chronic underfunding has severely impacted the quality of government schools, which are often understaffed and overcrowded. At the elementary level, there were 55 students for each teacher in public schools compared with just 22 students per teacher in private schools.

At elementary, secondary, and BTVET schools, the academic year runs from February to late November or early December. The school year is divided into three terms, with end-of-year examinations held in October or November.

At the tertiary level, the academic year runs from August to May and is divided into two semesters. Each semester consists of 15 weeks of teaching and two weeks of examinations.

Uganda’s official languages are English and, as of 2005, Swahili. However, a rich variety of local languages is used most frequently in everyday affairs throughout the country, a reality only recognized in the country’s educational system in the 21 st century.

Following the introduction of a local language policy in 2007, the first three years of elementary education are taught in the prevailing local language, after which English becomes the principal language of instruction. At the secondary level, all education is in English. The local language policy was initially greeted with enthusiasm, but it has proven hard to effectively implement because of the nation’s numerous ethnic and linguistic groups and a lack of learning materials and trained teachers in many minority languages.

Despite dramatic transformations, the current educational system of Uganda still bears the distinct imprint of its colonial past. Prior to the 1920s, most formal, basic education was in the hands of religious missions, both Catholic and Protestant. As elsewhere, missionary education in Uganda initially focused on basic literacy, guided by a missionary zeal to expand access to the holy scriptures. The influence of religion is still apparent in Uganda’s educational infrastructure. In 2017, more than half of all elementary schools in the country were founded by Catholic or Protestant missions, although most elementary schools are now owned and funded by the Ugandan government.

The colonial state began to take a more active interest in education in the 1920s. In 1922, it founded the nation’s first vocational training school, the Uganda Technical College, which would later become Makerere University. Three years later it established the nation’s first department of education, which mandated the use of the British school curriculum and education structure at all schools, a pattern that has largely continued to the present day.

School education in Uganda consists of three levels of varying length: seven years of elementary, four years of lower secondary, and two years of upper secondary education. Elementary education is the only compulsory level, and, since the introduction of UPE, is free for all Ugandan children age six to 13. Upon successful completion of the seventh year of education, and the passing of the Primary Leaving Examination (PLE), students are awarded the Primary School Leaving Certificate.

The National Curriculum Development Center (NCDC) designs and publishes a standard national curriculum for use at all UPE elementary schools. The curriculum for the seven years (Primary 1 to Primary 7, or P1 to P7) of Ugandan elementary education is divided into three cycles: Lower Primary (P1-P3), Transition (P4), and Upper Primary (P5-P7). The curriculum seeks to provide a holistic education, developing both the academic skills and personal values of students.

The content of the curriculum for grades one to three (P1-P3) is organized around themes familiar to young students, such as community, food and nutrition, recreation, festivals and holidays, and so on. Classes are, where possible, taught in the local language.

Starting in grade four, the curriculum is reorganized around traditional academic subjects, such as English, mathematics, science, and religious studies. English is gradually introduced as the primary language of instruction in grade four (P4), before its exclusive use in grades five through seven (P5-P7).

At the end of the seventh year of education, students sit for the mandatory—and high-stakes—Primary Leaving Examination (PLE) administered by the Uganda National Examination Board (UNEB). Sitting for the examination is a requirement for students who wish to proceed to secondary school and some vocational programs. Although secondary schools cannot deny spots to students on the basis of their PLE scores, students must meet a minimum threshold to qualify for a government-funded secondary seat under the Universal Secondary Education (USE) program. Students passing the PLE are awarded the Primary School Leaving Certificate.

Pre-elementary education is also available to young children, typically between the ages of three and six. In recent years, the Ugandan government has prioritized the promotion and development of early childhood education. In 2016, Uganda launched the National Integrated Early Childhood Development Policy Action Plan (2016-2021) of Uganda to raise awareness among families and caregivers of the value of early childhood development programs and to coordinate relevant sectors to help “ensure equitable access to quality and relevant ECD services for holistic development of all Children from conception to 8 years.”

Despite the government’s growing interest, participation rates remain low. According to UIS, Uganda’s pre-elementary gross enrollment ratio was just 14 percent in 2017, well behind regional neighbors such as Kenya, where more than three-quarters of the relevant age group are enrolled in pre-elementary schools. And despite growth in recent years, in 2017 there were still only 7,210 Early Childhood Development Centers (ECDs). The system is also plagued by regional discrepancies, with ECDs concentrated in urban areas, such as Buganda, where nearly two in five ECDs are located, and less prevalent in outlying, rural regions.

The secondary education cycle in Uganda lasts six years and consists of the eighth through 13th years of study, or Senior 1 (S1) through Senior 6 (S6). The cycle is split into two levels: lower secondary, which lasts for four years, and upper secondary, which lasts for two. Owing to the system’s British roots, these two levels are also known as the Ordinary and Advanced Levels, respectively. Secondary education is not compulsory, but for students eligible for the USE or UPOLET programs, it is available free of tuition. Despite these programs, overall enrollment rates, as discussed above, remain low.

The Ordinary Level, or O Level, curriculum lasts for four years, S1-S4. The NCDC-mandated curriculum includes four categories of courses, taught in English: science and mathematics, languages, social sciences, and vocational subjects. Compulsory science and mathematics courses include biology, chemistry, physics, physical education, and mathematics. Among language courses, only English is compulsory. However, Kiswahili, and other local and foreign languages, are available for optional study at some schools. For the social sciences, only geography and history are compulsory. Optional vocational subjects are offered in a number of subjects, including commerce, fine art, home economics, wood, and metalwork.

Upon successful completion of Ordinary Level classes, Ugandan students sit for the Uganda Certificate of Education (UCE) examination, which has been administered since 1980 and is currently managed by the Uganda National Examinations Board (UNEB). In the UCE examination, students are required to sit for a minimum of eight and maximum of 10 subject examinations. Six subjects are mandatory: English, mathematics, geography or religious studies, biology, chemistry, and physics. For the remaining two to four examinations, students can choose from a range of cultural, technical, and other subjects.

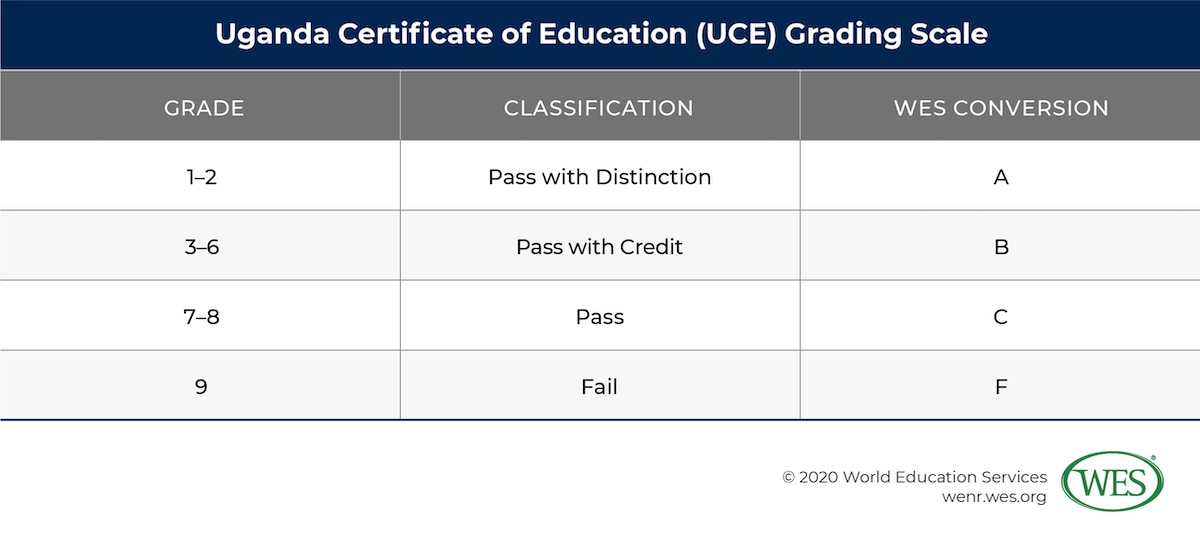

UNEB evaluates UCE examination subjects on a 1 to 9 grading scale. Grades 1 and 2 are passes at the highest level, “Distinction.” Grades 3, 4, 5, and 6 are “Credit” passes. The last passing grades are 7 and 8, which are classified at the “Pass” level. A grade of 9 results in a failure. Again, this system of external examination and graded classification has its roots in Uganda’s colonial past and is common in many Commonwealth countries.

The overall pass rate of students taking the UCE examinations has risen in recent years, with 92 percent passing in 2019, a significant improvement from the 87 percent passing rate the year before. UCE participation has also increased markedly. Between 2015 and 2019, the number of candidates sitting for UCE examinations increased by 9 percent.

The Uganda National Examinations Board (UNEB) awards the Uganda Certificate of Education (UCE) to students passing their UCE examinations. Possession of the UCE is a requirement for admission to Advanced Level studies. Students successfully passing the UCE examinations can also move on to teacher training programs, vocational education, or into the workforce.

The final two years of the secondary education cycle, S5 and S6, are known as Advanced Level, or A Level. They culminate in the Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education (UACE) examinations, the prerequisite for entrance to universities in Uganda. These examinations are held annually in November and December.

UACE candidates must sit for five subject examinations, two at the subsidiary level and three at the principal level. At the subsidiary level, all students must sit for the general paper, and may choose between either subsidiary mathematics or subsidiary computer (also known as subsidiary information and communications technology). At the principal level, students are able to choose from a wider range of subjects, with decisions often made with future university studies in mind. Principal-level subjects include history, economics, physics, and foreign and local languages and literature, among others.

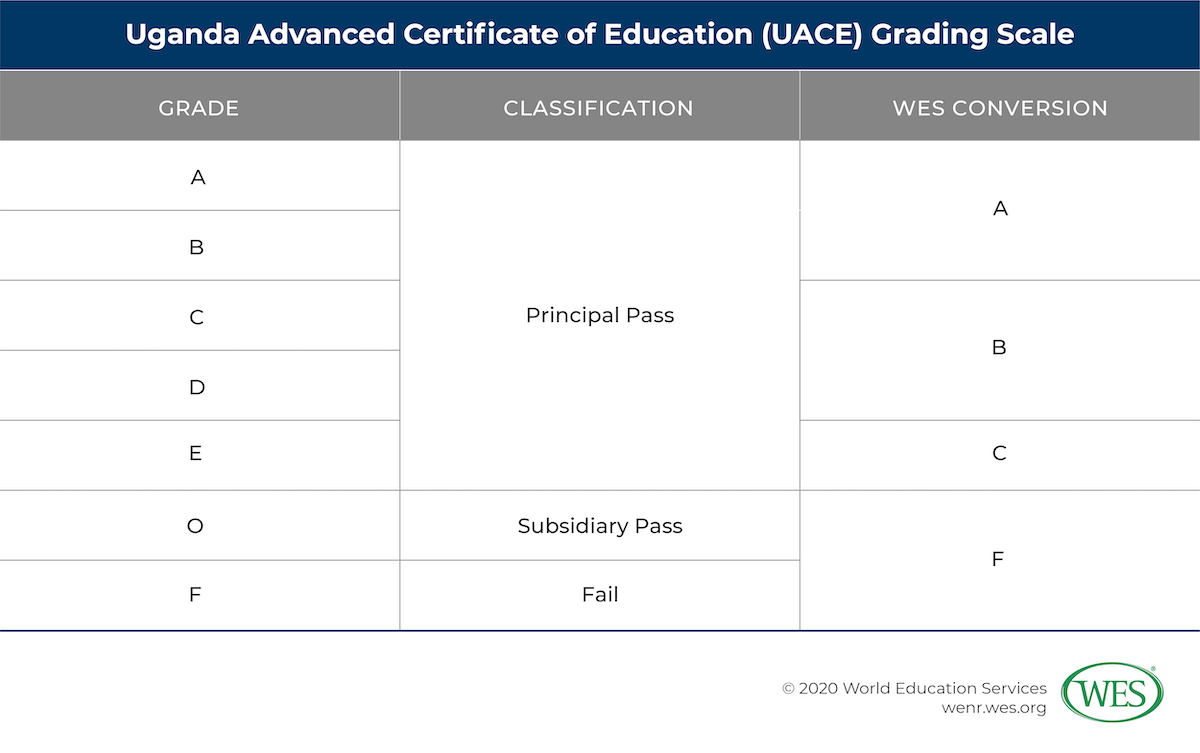

The grading system used for principal and subsidiary subject examinations differs slightly. Principal-level subjects are graded on a seven-point, A through F scale, with letter grades further categorized into three groups: Principal Pass, Subsidiary Pass, and Fail. An A is the highest Principal Pass grade, and an E, the lowest; an O is a Subsidiary Pass grade; and an F, a failing grade. Subsidiary-level subject examinations are graded on a 0 to 6 scale. Under this system, a 6 is the highest and a 1 the lowest Subsidiary Pass grade, while a 0 is a failing grade.

The Uganda National Examinations Board (UNEB) awards the Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education (UACE) to students who earn at least one Principal Pass, or at least one Subsidiary Pass in a subject taken at the principal level. Students graduating with the UACE can enter the workforce or proceed to higher education.

However, not all holders of the UACE qualify for university seats, as at least two Principal Passes are required for university admission. While the overall pass rate for the UACE examination is remarkably high, nearly 99 percent in 2019, far fewer meet the minimum entry requirements of Uganda’s universities. Less than two-thirds (64 percent) of students passing the UACE examination in 2019 qualified for university admission.

Despite the importance of technical and vocational education and training (TVET) to both Uganda’s current agricultural economy and its expected, future oil-based economy, the TVET sector in Uganda faces significant challenges. While the government has attempted reforms, a long history of underfunding, mixed messaging, and overlapping jurisdictions have left the sector underutilized and ill regarded. But growing interest in oil- and gas-related technical education and rising enrollment numbers may hint at a brighter future.

Uganda’s TVET sector has long faced challenges. As late as 2011, more than 60 percent of large and medium-size businesses in Uganda considered the content and teaching methods of the country’s vocational institutions irrelevant to the needs of the modern economy, according to a UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning report.

The government attempted to improve the sector in the Business, Technical, Vocational Education and Training (BTVET) Act of 2008. The act’s sponsors hoped that the act would coordinate the country’s unwieldy TVET sector by establishing regulatory bodies and qualification and competency frameworks.

However, studies suggest that the act has done little to improve the sector’s quality. A 2018 analysis funded by the International Development and Research Center (IDRC) found that funding remained too limited to adequately staff and provide for vocational institutions.

Furthermore, although the act invested a number of boards with the exclusive authority to regulate vocational education throughout the country, institutions offering TVET programs are often able to avoid this regulatory oversight. The same IDRC-funded analysis found that many institutions offering TVET programs were taking advantage of ambiguous oversight regulations to claim the privileges of universities. This allowed them to develop their own courses and conduct their own examinations unsupervised by the relevant regulatory bodies. As a result, institutions have effectively abandoned the institutional framework established under the BTVET Act and begun offering their own courses and examinations under less restrictive provisions intended for tertiary education providers.

Despite these challenges, the TVET sector’s fortunes may be improving. Once low, enrollment in programs regulated by the official bodies established under the BTVET Act of 2008 is starting to take off. The number of candidates registered in examinations conducted by the Uganda Business and Technical Examinations Board (UBTEB) have more than tripled since 2015, growing from just under 25,000 to over 80,000 in 2019. And the Petroleum Authority of Uganda (PAU), the governmental organization responsible for the regulation of the country’s petroleum industry, has determined that most of the training needed to develop the sector’s workers should be conducted in the country’s TVET institutions.

Following completion of a BTVET course of study, students sit for external examinations administered by the relevant examination board. The Uganda Business and Technical Examinations Board (UBTEB) is responsible for business, vocational, and technical programs, the Uganda Nurses and Midwives Examinations Board (UNMEB) for nursing and midwifery programs, and the Uganda Allied Health Examinations Board (UAHEB) for paramedical sciences. The Directorate of Industrial Training (DIT) is responsible for accrediting TVET institutions as Uganda Vocational Qualification Framework (UVQF) assessment centers.

These examination boards award both certificates and diplomas. Certificate and diploma qualifications are further divided into several sub-qualifications. Under the current BTVET scheme, certificate candidates passing their final examinations are awarded either National Certificates, Junior Vocational Certificates, or Competence National Certificates. Likewise, diploma-level graduates are awarded either National Diplomas or Higher Diplomas.

The Uganda Business and Technical Examinations Board (UBTEB) administers examinations for the certificate and diploma programs described below. The National Curriculum Development Centre (NCDC) designs and publishes the curricula for many of these programs, which involve far more practice, such as laboratory work or hands-on experience, than curricula for academic primary, secondary, and tertiary programs.

The 2008 BTVET Act, in addition to creating the institutional framework outlined above, mandated the establishment of a “qualifications framework based on defined occupational standards and assessment criteria for the different sectors of the economy.” The Uganda Vocational Qualifications Framework (UVQF) divides vocational qualifications and competencies into five levels, with Higher Diplomas pegged at Level 5. However, as of publication, implementation of the UVQF appears limited, and it is not always clear to which level the different credentials correspond.

Competence, or Competency, National Certificates are the lowest level of TVET qualification offered in Uganda. The programs are aimed at students who have not completed elementary education, but who still require or desire additional skills to enter certain professions. These programs are as short as three months to as long as seven years and are typically offered in agricultural subjects.

National Junior Vocational Certificates, more commonly known as Uganda Community Polytechnic Certificates (UCPCs) or Junior Vocational Certificates, are three years in length and are equivalent to the Uganda Certificate of Education. Entry is restricted to students passing the Primary Leaving Examinations.

National Certificate programs are two years in length and are at the same level as the Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education. Entry to a National Certificate program requires the Uganda Certificate of Education or an equivalent qualification. A range of subjects are offered at the National Certificate level, such as cosmetology and beautification, mechanical engineering, and business studies.

Technical Craft Certificates, also known as Craft Certificates Part II, last two years and require the Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education or its equivalent for entry. They lead to the one-year Technical Advanced Craft Certificates, also known as Craft Certificates Part III. These certificates aim at training competent technicians and are offered in fields such as block laying and concrete practice.

National Diplomas are two-year, post-secondary qualifications, aimed at preparing graduates to enter the workforce or continue their studies in higher level vocational programs. Successfully passing the Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education is a requirement for admission. National Diplomas are offered in the fields of engineering and business.

Higher Diplomas are the highest level of TVET education offered in Uganda. They are two-year programs that follow completion of the National Diploma. They are offered in engineering subjects, such as mechanical, civil, and electrical engineering, among others.

A lack of qualified teachers has long been a problem in Uganda. As early as 1952, a committee convened by the colonial governor of Uganda identified as priorities “the reorganization and expansion of the system of teacher training” and the “improvement of the conditions and terms of service of teachers of all categories.”

With the increase of student enrollments following the introduction of UPE and USE, the need for trained teachers also increased. In response, the MoES, along with Enabel, a Belgian development agency, launched the Teacher Training Education (TTE) Project, which seeks to “strengthen professional competencies of teacher trainers and future teachers graduating from the National Teachers’ Colleges (NTCs) in Uganda.” The project focuses on secondary education.

The Teacher/Tutor, Instructor Education and Training (TIET) department within the MoES is responsible for the training of pre-elementary, elementary, secondary, and vocational teachers. It also ensures the quality of teacher education and distributes instructional materials for training institutions, recruits qualified teachers and trainees, and coordinates trainings. Teacher training institutes, such as a string of national teacher’s colleges, must be licensed and registered with the MoES. The MoES also sets admission requirements and curricula for all programs nationwide. Admission requirements differ based on the educational level at which the trainee intends to teach.

Pre-primary Teacher Education and Training: Admission to pre-primary teacher education and training requires students to have successfully completed their O Level studies. The period of education and training lasts two years. Upon completion of the program, students are awarded Certificates of Completion from their training institute and are registered with the MoES.

Primary Teacher Education and Training: Admission to primary teacher education and training programs requires completion of O Level examinations with a minimum of six passes. The program includes two years of pre-service training, followed by three years of in-service training. The curriculum includes both practical and theoretical content, combining supervised, on-site training with desk-based research and examinations. Trainees attend primary teachers’ colleges (PTCs), with the government paying all tuition fees provided students remain in good academic standing. Students must register with Kyambogo University—the only institution authorized to examine and award primary teachers’ qualifications—to sit for the mandatory end-of-year examinations. Upon successful completion of the training program, trainees are awarded Grade III Teacher Certificates by Kyambogo University.

Secondary Teacher Education and Training: The MoES requires that students admitted to secondary teacher education and training programs complete their A Level examinations with at least two passes at the principal level in art subjects, or at least one pass at the principal level in science subjects plus two passes in any subject at the subsidiary level. Training is conducted at National Teachers Colleges and requires two years of study. Successful trainees are awarded Diplomas in Secondary Education, after which they are registered with the MoES as Grade V teachers.

Certain universities also offer undergraduate teaching programs of three to four years in length. Admission requires two A Level passes at the principal level in any arts, science, or vocational subjects. Graduates are awarded a Bachelor of Education and are registered with the MoES as graduate teachers.

Uganda’s higher education system, once the envy of East Africa, is in dire straits. Strikes and protests by students, faculty, and staff over late pay, low salaries, tuition hikes, and safety concerns rock Ugandan universities year after year. Each semester, more and more students crowd into lecture halls and student housing built decades ago, as facility upgrades and new construction projects lag significantly behind growing student numbers. Low and late pay and a lack of academic freedom have made qualified professors hard to find and led to growing corruption, with degree forgery scandals rocking even the country’s top university.

Exacerbating these issues are the same challenges facing other levels of Ugandan education: rapid population growth and inadequate public funding. These concerns have led Ugandan reformers to call on the government to significantly increase its support of the country’s higher education institutions if there is to be any hope of saving its universities. So far, there has been little response to those calls.

Demand for higher education in Uganda has increased significantly over the past several decades, a result of rapid population growth and rising elementary and secondary enrollment rates. Enrollment in post-secondary institutions grew from around 5,000 in the 1970s to almost 125,000 in the 2005/06 academic year. A decade later, enrollment had nearly doubled, growing to more than 250,000 in 2015/16, the latest year for which enrollment data are available.

This relative “massification” of Uganda’s higher education system has severely strained the country’s higher education infrastructure. Lecture halls and student housing units are overloaded, teaching facilities and materials are inadequate, qualified professors are in short supply, and educational outcomes are poor.

Furthermore, despite congested classrooms, overall access remains limited. In the 2015/16 academic year, the percentage of college-age Ugandans actually enrolled in a higher education institution stood at under 7 percent, according to NCHE data, compared with a world average of around 37 percent. Low secondary enrollment and graduation rates and poor performance on compulsory entrance examinations account for some of the low enrollment rates at Ugandan universities. But the country’s shortage of available university seats is also a significant obstacle to higher enrollment rates. In 2011, there were only 30,000 vacant university seats for the more than 60,000 qualifying secondary school graduates. Professor A. B. Kasozi, head of the NCHE at the time, commented that, in general, Ugandan universities have the capacity to admit just 20 percent of applicants.

Access is also far from equitable. Since the 1990s, much of the responsibility for covering the cost of higher education, at both public and private universities, has shifted from the government to private families. By 2004, Ugandan households contributed more than 50 percent of total national spending on higher education, one of the highest rates in Africa, according to a World Bank report. But the cost of a university education is prohibitively high for many of Uganda’s poorest students. And the Higher Education Student Financing Board (HESFB), created in 2014 to fund grants and scholarships for Ugandan university students, has, since its inception, been underfunded and criticized for overlooking the country’s poor.

Furthermore, the concentration of university campuses in the region around the capital makes access even more difficult for students from outlying regions, who tend to be poorer than their peers living elsewhere. The distance forces these students to incur additional travel and housing costs.

Despite these issues, the government funding necessary to relieve the pressure on Uganda’s universities and college students has not been forthcoming. Public funding has lagged far behind the growing demand for higher education, forcing universities to spend less to educate more students. The World Bank report estimated that Uganda would have had to increase its spending on higher education by more than 50 percent to adequately support the increase in students between 2006 and 2015. As of 2006, Uganda was one of the lowest spending countries per higher education student in Africa, the report also found, a problem that has likely improved little over time.

The origin of Uganda’s modern higher education system can be traced back to 1922, with the establishment of what would eventually become Makerere University, one of the oldest English-speaking universities in Africa. Founded as a technical school, it initially sought to prepare Ugandan students for positions in the colonial administration. It began to offer degree programs in 1949, when it became a university college affiliated to the University College of London (now known as UCL). In 1970, it became a full-fledged national university, offering and awarding its own undergraduate and postgraduate programs.

Makerere University’s high academic standards and solid research output have earned it a reputation as one of Africa’s premier institutions of higher education, with many dubbing it the “Harvard of Africa.” Over the years the university educated many of the continent’s most important political leaders. Although the university’s students, faculty, and quality suffered severely under the Amin and Obote II regimes, its reputation rebounded following Museveni’s rise to power in 1986.

But the university has not been spared the more recent troubles afflicting Uganda’s higher education system as a whole. The issues stem from a trend of privatizing public services that swept the continent, and both the Ugandan government and Makerere University, in the 1990s, just as demand for higher education began to rise.

Prior to 1994, the Ugandan government funded the study of all students attending Makerere University. But the government’s reluctance to increase funding meant that the university could not raise enrollment levels enough to meet the nation’s growing demand for higher education. In response, the university, which was and is led by a presidential appointee, introduced an innovative financing strategy, the acceptance of fee-paying students.

This move toward privatization, one of the first in Africa, was lauded by the international financial community and helped increase enrollment significantly. Between the mid-1980s and mid-2000s, enrollment at Makerere University grew from around 5,000 to more than 40,000, a level it has since maintained. The university also went from the government paying tuition and room and board fees for all its students, to 70 percent of its students paying fees.

But the funds, from both the government and private tuition fees, proved insufficient to support an expansion in teaching facilities and infrastructure. More than a quarter century after the reforms, overcrowded lecture halls and student dormitories remain a concern, with reports of hundreds of students cramming into classes intended for fewer than 50. Tuition fee hikes, necessary to prop up university finances in lieu of further government funding, spark protests and, at times, arrests by police. Faculty and staff likewise strike for better pay and working conditions.

Despite these challenges, Makerere University remains one of the continent’s top higher education institutions. Times Higher Education ranked Makerere University the third best university in Africa in 2017, trailing just two South African universities. But the issues outlined above are taking a toll. Just two years later, it had fallen to 11 th , tied with eight other African universities. Whether university and government leaders can reverse the decline—the university plans to reduce private student enrollment in the coming years—remains to be seen.

Until 1988, Makerere University was the only Ugandan tertiary institution authorized to award degrees. In the years that followed, the number of higher education institutions in Uganda expanded rapidly. Currently, there are more than 50 accredited universities, both public and private, plus nearly 200 institutions authorized to award post-secondary certificates and diplomas. With government funding for higher education stagnating, private universities and institutions have seen the most growth. As of publication, the NCHE website listed 46 private accredited universities.

Higher education institutions in Uganda are divided into three categories: universities, other degree- awarding institutions (ODAIs), and other tertiary institutions (OTIs). Accredited universities are authorized to award certificates, diplomas, and undergraduate and post-graduate degrees. ODAIs are authorized to award certificates, diplomas, and specific undergraduate and post-graduate degrees. OTIs are authorized to award certificates and diplomas.

OTIs include various colleges that specialize in business, teacher training, health sciences and nursing, and technical subjects, among others. All three types include both public and private institutions. Although there are far more private universities than public universities in Uganda–there were only eight public universities in 2019/20–public universities, which also accept fee-paying students, enroll the majority of students.

Tuition fees are very important to Ugandan universities, both public and private. Universities in Uganda generate 56 percent of their income from tuition and other fees, according to the World Bank report mentioned earlier. Tuition fees for privately funded students range from around UGX700,000 (US$190) to UGX2,000,000 (US$540) per semester. With the decline in government funding, public universities have turned to private sources, whether tuition fees or donors, for operating and research funds. While public universities still offer some fully or partially government-funded university seats, most students at public universities are privately funded. As of 2010, just a quarter of all students at public universities were government funded, according to the World Bank.

Naturally, tuition fees are even more important at private universities. As around three-quarters of their funding comes from tuition fees, maintaining a high level of enrollment is an ever present, if elusive, necessity. As a result, failure rates for private institutions are notoriously high.

Uganda’s National Council for Higher Education (NCHE), established in 2001, is responsible for regulating Uganda’s tertiary education sector to ensure that all of the country’s higher education institutions provide a high-quality education. It oversees the accreditation and quality assurance of all higher education institutions and programs, both academic and professional, in Uganda. The NCHE is also responsible for setting nationwide admission standards, collecting and distributing information on the Ugandan higher education system, and advising the government on relevant education policies.

All academic and professional programs at every higher education institution, both public and private, must be accredited by the NCHE before those institutions can begin to teach. After the initial accreditation, the NCHE reviews the program every five years to ensure that it still meets at least minimum quality standards. If it does, NCHE reaccredits the program for an additional five years. If the NCHE does not review and reaccredit a program every five years, the program automatically loses its accreditation, and the institution must stop offering the program to its students.

But despite statutory requirements, not every program taught at a Ugandan higher education institution has been accredited by NCHE. During the 2017/18 academic year, Ugandan universities illegally offered more than 1,000 academic programs not accredited by the NCHE. To clarify the accreditation status of higher education courses, the NCHE publishes a list of currently accredited programs and institutions on its website.

Admission to Ugandan higher education institutions is merit-based, with minimum entry requirements set by the NCHE. Government-funded seats at public universities are also merit-based, although quotas exist to ensure that all of the country’s 127 districts have access to publicly funded university spots.

Graduates from Uganda’s secondary schools are able to apply to undergraduate degree programs through two entry schemes, diploma and indirect. The diploma option allows holders of a diploma passed at the distinction or credit level to obtain lateral entry to a university program. The course of study must have been relevant to the undergraduate academic program and must have been pursued at an institution accredited by the NCHE.

In general, to qualify for direct entry, an applicant must hold both a Uganda Certificate of Education (UCE) with a minimum of five passes and a Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education (UACE) with a minimum of two Principal Passes. But the specific requirements for different undergraduate degree programs vary widely, requiring differing levels of success in certain UCE and UACE examination subjects relevant to the undergraduate program. The MoES publishes the program-specific admission requirements of public universities each year in a comprehensive guide known as the Information on Public University Admissions. The guide also outlines the detailed weighting system used to evaluate the relevant academic performance of applicants.

For applicants age 25 years or older who have not completed O Level or A Level examinations, there is the mature entry scheme. These students must pass a rigorous Mature Age Entry Examination at 50 percent or higher to qualify for university admission.

Admissions officers weigh the UCE and UACE scores achieved by an applicant according to a detailed “weighting system” determined by the MoES. Principal-level subjects are grouped into three weighted categories—essential, relevant, and desirable—according to their level of relevance to the undergraduate degree program a student is applying for. Essential subjects are given a weight of 3, relevant subjects, 2, and desirable subjects, 1. Letter grades are then converted to a numeric, 0 to 6 scale, with an A equivalent to 6 and an F equivalent to 0. An admission score for each principal-level examination is then determined by multiplying the relevance score by the grade score. UACE subsidiary level and UCE examination scores are not weighted by relevance and play a much less important role in determining an applicant’s admission eligibility. Passes in UACE subsidiary-level subject examinations are given a score of 1. For UCE examinations, Distinction, Credit, Pass, and Failing grades are given scores of 0.3, 0.2, 0.1, and 0.0 respectively. An applicant’s combined admission score is then determined by adding a student’s admission scores for all UACE principal, subsidiary, and UCE subjects.

Ugandan higher education institutions offer a range of programs and issue a variety of credentials. The curricula of programs at all levels require both academic and practical training, such as internships, with the balance between the two ideally determined by the nature of the program. Besides examinations, most require the completion of major written reports or dissertations.